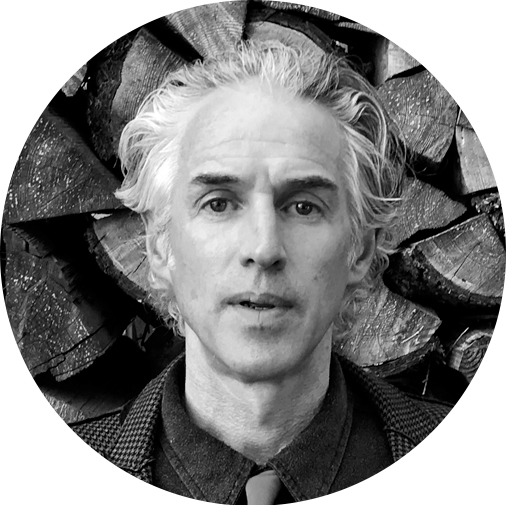

Prof. Jules Boykoff

Professor and Politics and Government Department Chair at Pacific University. He teaches political science. Jules is author of six book on the politics of the Olympics, most recently, What Are the Olympics For?

Email: boykoff@pacificu.edu

Twitter: @JulesBoykoff

When activist Natsuko Sasaki took the stage at the “Counter-Opening Ceremony of the Olympics” the evening before the official opening of the Paris 2024 Summer Games, she had a special surprise. Partway through her remarks in front of more than a thousand people gathered at Place de la République, the activist with the group Saccage 2024 revealed that she possessed the “Anti-Olympics Torch.” First created in Vancouver to protest the 2010 Winter Olympics, the alternative torch had wended around the world, bouncing to London, Rio de Janeiro, and Tokyo. The torch, a toilet plunger decorated with cloth ribbons displaying anti-Games slogans made by groups in numerous Olympic cities, symbolized resolute international resistance to the Olympics, regardless of host city.

Sasaki was speaking at an event featuring more than eighty grassroots organizations, from environmental groups to trade unions to civil-liberties collectives. Ahead of the event, these groups released a joint statement “Des Jeux, mais pour qui?” (“Games, but for whom?”). Members of the watchdog group Vigilance JO [Jeux Olympiques] Saint Denis were present with banners and fliers on issues related to Saint Denis, the area in northern Paris that featured the Olympic Village which received a sharp dose of gentrification from hosting the Games. Groups were supplemented by hundreds of pro-Palestinian activists waving flags and asking why Israel was allowed to participate in the Paris Games, despite the ravages it was inflicting on Gaza. One sticker affixed to an activist’s shirt sleeve read, “Genocide Is Not An Olympic Sport.”

One of the prime movers behind activism challenging the Paris Olympics was the activist collective Le Revers de la Médaille (the Other Side of the Medal). The group zeroed in on the displacement processes that intensified ahead of the Olympics, and continued during the Games themselves. They dubbed this “nettoyage social,” or social cleansing. Paul Alauzy, a spokesperson for the group, explained, “In Paris, the social cleansing can be understood with a double logic of dispersion: a dispersion within the Olympic city’s public space, to avoid tent cities, slums, squats, and disperse the marginalized people, and a dispersion within the whole country, so that to delocalize the unwanted and push the misery away from the Olympic city.”

Security forces in the Olympic host country also take advantage of the exception the Games bring to militarize weapons stocks done to protect the Olympic spectacle from terrorist attacks. However, the same weapons and control tactics can also be wielded against activists. This dynamic unfolded in Paris on 28 July 2024 when Noah Farjon, an anti-Olympics activist with Saccage 2024, was in the process of shepherding two journalists toward a “Toxic Tour” of Saint Denis led by Natsuko Sasaki.

These Toxic Tours are mobile informational events involving journalists, local advocates, and others that enable them to better understand the impacts that the Paris 2024 Games were having on working-class people in Saint Denis. Before the journalists and activist were able to join the group for the tour, four police cars blocked them as they emerged from the Saint Denis-Porte de Paris Metro stop. After carrying out identity check and physical searches, the police discovered hand-outs and stickers critical of the Olympics. The police arrested all three of them—including the journalists—and brought them into custody, where they stayed for 10 hours. Their charges were eventually dropped. After his release, Farjon said that the Paris Games instigated “a lockdown on dissent” and that “Paris is basically under occupation.” A few days later, Farjon was arrested again while organizing another Toxic Tour this one focused, ironically, on police repression.

Modern-day anti-Games campaigns typically bring together already-existing movements and advocates into temporary coalitions that pool resources to contest the political logic of the Olympics. This has made anti-Olympics organizing more of an extended moment of movements than a movement of moments, per se. As such, anti-Olympics activism is less a social movement and more what political scientist Sidney Tarrow calls an event coalition: a temporary convergence of activist organizations that coalesce around common goals, tactics, and strategies during a particular episode of contention.

In recent years, though, activists have moved to create a transnational social movement that transcends a particular host city and is sustained between Games. With leadership from anti-Games groups in Tokyo and Los Angeles, activists staged the first-ever transnational anti-Olympics summit in Tokyo in 2019. Activists converged to share stories and strategies emerging from their battles in Japan, South Korea, France, Brazil, England, the US, and elsewhere. This was followed by a second international summit in Paris in 2022.

Activists in Los Angeles from the group NOlympicsLA are prime movers in this milieu. They issued a solidarity statement with activists in Paris. With the Los Angeles 2028 Summer Olympics on the horizon, anti-Games activism will continue to be an important political dynamic to track.