Dr Sae Oshima

Senior Academic in Corporate and Marketing Communications at Bournemouth University (UK). She is a trained microethnographer of social interaction. Her research reveals the micro-foundations of societal phenomena, pursues business outcomes as interactional projects, and proposes implications for training in workplaces.

Twitter: @saeminh

Section 2: Media Coverage & Representation

- Twitter conversations on Indian female athletes in Tokyo

- ”Unity in Diversity” – The varying media representations of female Olympic athletes

- The Olympic Channel: insights on its distinctive role in Tokyo 2020

- How do we truly interpret the Tokyo Olympic ratings?

- Between sexualization and de-sexualization: the representation of female athletes in Tokyo 2020

- Reshaping the Olympics media coverage through innovation

- An Olympic utopia: separating politics and sport. Primary notes after analyzing the opening ceremony media coverage of mainstream Spanish sport newspapers

- What place is this? Tokyo’s made-for-television Olympics

- The paradox of the parade of nations: A South Korean network’s coverage of the opening ceremony at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics

- Tokyo 2021: the TV Olympics

- Why we need to see the “ugly” in women’s sports

- “The gender-equal games” vs “The IOC is failing black women”: narratives of progress and failure of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics

- Ghana: Poor local organizing, and absence of football team dampens interest

- Megan Rapinoe: The scary Bear for many Americans?

- ‘A Games like no other’: The demise of FTA live Olympic sport?

- Fandom and digital media during the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games: A Brazilian perspective using @TimeBrasil Twitter data

- Media wins medal for coverage of athletes as people, instead of entertainers

- Media frames and the ‘humanity’ of athletes

- Reporting at a distance. Stricter working conditions and demands on sports journalists during the Olympics

- New Olympic sports: the mediatization of action sports through the Olympic Games 2020 Tokyo

- Simone Biles, journalistic authority, and the ideology of sports news

- Representations of gender in the live broadcast of the Tokyo Olympics

- Americans on ideological left more engaged in Summer Olympics

- Nigeria: Olympic Games a mystery for rural dwellers in Lagos

- National hierarchy in Israeli Olympic discourses

- Equestrian sports in media through hundred Olympic years. A roundtrip from focus to shade and back again?

- Reshaping the superhuman to the super ordinary: The Tokyo Paralympics in Australian broadcasting media

- Is the Paralympic Games a second-class event?

- The fleeting nature of an Olympic meme: Virality and IOC TV rights

- Tokyo 2020: A look through the screen of Brazilian television

- Is the Paralympic Games a second-class event?

- How digital content creators are shaping meanings about world class para-athletes

- How digital content creators are shaping meanings about world class para-athletes

- The male and female sports journalists divide on the Twittersphere during Tokyo 2020

- Super heroes among us: A brief discussion of using the superhero genre to promote Paralympic Games and athletes

- “Everything seemed very complicated”: Journalist experiences of covering the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games

- Representing high performance: Brazilian sports journalists and mass communication professionals discuss their philosophies on producing progressive Paralympic coverage

- Representations of gender in media coverage of the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games

Sports commentators do not “just” comment. Through delivering commentary, they may negotiate their areas of expertise, construct dramatic events, or construct/reconstruct stereotypes. What follows are my preliminary, micro-ethnographic observations of one such activity that sports commentators engage: discovering and/or constructing emotions in athletes. The following 3 examples are from the Judo matches of the Japanese Abe siblings, aired during the BBC’s 2020 Olympics coverage, Day 2: BBC One 12:15-15:00. Two live commentators narrated the matches, who I refer to as C1 and C2. In performing conversation analysis, I apply Paul ten Have’s transcript conventions.

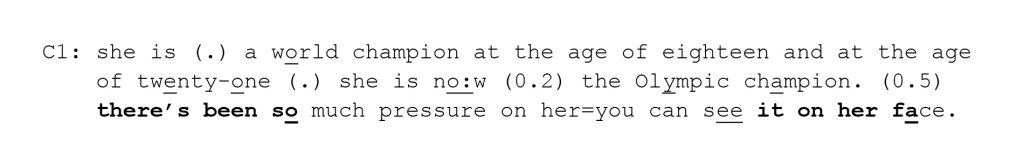

Generally speaking, live, play-by-play sports commentators provide backstory, observations, and accordingly, interpret an athlete/team’s inner state in real-time. See, for instance, how C1 contextualizes Uta Abe’s facial expression at the time of her victory (found at 2:35.25 in the abovementioned clip):

During this comment, Abe’s mixed (smiling/crying) facial expression appears twice on the screen (where the transcript is bolded). When it first appears, C1 speeds up by connecting her two sentences without pause (“her=you”), emotionalizing Abe’s real-time actions while the visual reference is still fresh among viewers (or accessible, as it ends up appearing again).

However, C1’s comment is not only about this particular moment; it packages the larger scale of Abe’s emotional journey – “so much pressure” that she must have experienced in her past few years – into this momentary facial expression. Indeed, the work of emotionalizing may connect the audience to multiple points of emotional states that athletes supposedly go through.

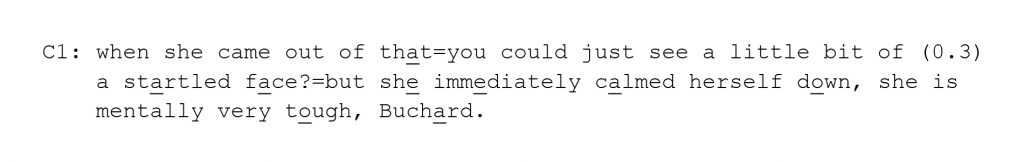

Going back to a moment before Abe wins, there is a scene where her competitor, Amandine Buchard, comes out of a tackle made by Abe. The camera briefly catches Buchard’s facial expression that may indicate concern or nervousness (2:30.02). Nine seconds later (2:30.11), C1 labels it as a state of being “startled”:

C2 had been talking during the 9 seconds prior, so it is natural that C1’s observation was offered in a later turn. Yet, this “delay” achieves something else. It is precisely 9 seconds later – where the referred expression disappears and Buchard has re-oriented herself to the game – that it becomes possible for C1 to retrospectively interpret the expression and contextualize it around her current state of having “calmed down”; being “startled” is no longer a negative affair, but acts as the evidence for the claim that “she is mentally very tough”. Buchard’s process of composing herself would not have been embodied in the same way had C1 commented on the initial “startled” expression separately, as it was happening.

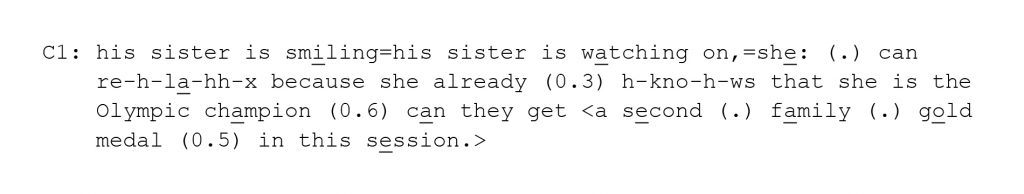

The athlete’s (constructed) emotional state can also be prolonged with live commentary. Immediately after the above mentioned match was the gold medal contest of Uta Abe’s brother, Hifumi Abe and Vazha Margvelashvili. The already-crowned Olympic champion sister watches from the sidelines, and the camera catches her smile in the middle of it (2:38.15 & 2:38.17).

A few seconds after the smile was on the screen, C1 emotionalizes it (2:38.19):

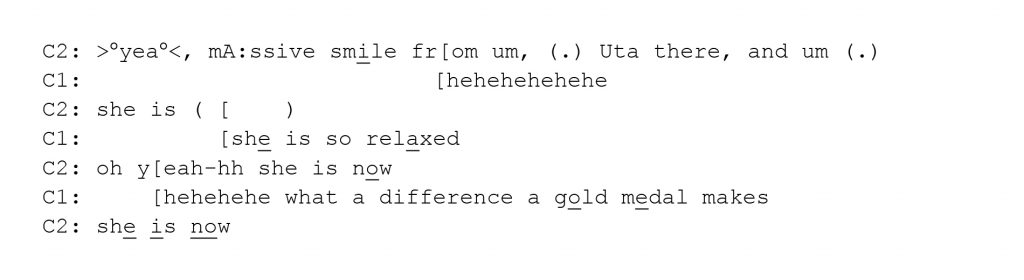

Abe’s smile is long gone from the viewers by the time C1 finishes her comment, and C1 slows her delivery and uses a falling intonation at the end, which could suggest the topic closure. However, C2 immediately latches on and re-topicalizes the smile (2:38.33):

C2 not only revives Abe’s constructed emotion, but upgrades it with the adjective, “massive”. This renewed assessment creates room for C1 to react to and revisit its meaning (Abe is not just relaxed, she is “so” relaxed), which is picked up by C2, who adjusts it by emphasizing the “now”-ness of Abe’s relaxed state (in further contrast to her previous state). While these additional comments could well be a way of filling time while waiting for next “comment-able” moment, the prolonged topicalization gives space for the commentators to co-develop the meaning: from a smile of a relaxing sister, to a massive smile, to the kind of smile we viewers can only witness after someone has won an Olympic gold medal.

In one hand, emotionalizing athletes is about “what”, e.g. interpreting – or creating – emotions in athletes (which begs the question for another discussion: just how do live commentators socialize audience with what athletes ought to feel or not?). On the other hand, it is also about “when”. Emotionalization may be done on the spot, delayed, prolonged or revived, often packing multiple time-scales into a momentary action, such as a glimpse of a facial expression of an athlete. Such embodied temporalities provide audiences with various sense-making tools to experience the athletes’ emotional journey – regardless of it being discovered or constructed.