Dr Renan Petersen-Wagner

Senior Lecturer in Sport Business and Marketing at the Carnegie School of Sport and Researcher in the Centre for Social Justice in Sport and Society at Leeds Beckett University.

Twitter: @renanpwagner

Andressa Fontes Guimarães-Mataruna

Ph.D. Candidate in Journalism at University of Beira do Interior. She has MA International Relation – Peacebuilding from Coventry University, UK. She graduated in Science of Communication from UNESA, Brazil.

E-mail: andressa.mataruna@ubi.pt

Dr Adriano Lopes de Souza

Lecturer at the Physical Education Department, Federal University of Tocantins, Brazil. He specializes in the field of sociocultural studies of sports, particularly the Modern Olympic Movement and its Games.

E-mail: adrianolopes_10@hotmail.com

Dr Doiara Silva dos Santos

Graduated in Western University, Canada. Currently serving as a Lecturer at the Physical Education Department, Federal University of Viçosa, Brazil. She specializes in the field of sociocultural studies of sports, particularly the Modern Olympic Movement and its Games

E-mail: santosdoiara@ufv.br

Dr Leonardo José Mataruna-Dos-Santos

Associate Professor in the Department of Sport Management at the Faculty of Management – Canadian University of Dubai. He is an Associate Research at Coventry University and UFRJ-PACC. He is also member of STRADEOS research group of University of Lille and member of WADA Education Committee.

Email: leonardo.mataruna@cud.ac.ae

Prof Otávio Guimarães Tavares da Silva

Professor at the Federal University of Espírito Santo, Brazil. Director of the Centre of Physical Education and Sport and Leader of ARETE – Centre of Olympic Studies. He researches in the field of sociocultural studies of sports, with special interest in the Modern Olympic Movement.

E-mail: otavio.silva@ufes.br

Section 2: Media Coverage & Representation

- Twitter conversations on Indian female athletes in Tokyo

- ”Unity in Diversity” – The varying media representations of female Olympic athletes

- The Olympic Channel: insights on its distinctive role in Tokyo 2020

- How do we truly interpret the Tokyo Olympic ratings?

- Between sexualization and de-sexualization: the representation of female athletes in Tokyo 2020

- Reshaping the Olympics media coverage through innovation

- An Olympic utopia: separating politics and sport. Primary notes after analyzing the opening ceremony media coverage of mainstream Spanish sport newspapers

- What place is this? Tokyo’s made-for-television Olympics

- The paradox of the parade of nations: A South Korean network’s coverage of the opening ceremony at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics

- Tokyo 2021: the TV Olympics

- Why we need to see the “ugly” in women’s sports

- “The gender-equal games” vs “The IOC is failing black women”: narratives of progress and failure of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics

- Ghana: Poor local organizing, and absence of football team dampens interest

- Megan Rapinoe: The scary Bear for many Americans?

- ‘A Games like no other’: The demise of FTA live Olympic sport?

- Temporality of emotionalizing athletes

- Media wins medal for coverage of athletes as people, instead of entertainers

- Media frames and the ‘humanity’ of athletes

- Reporting at a distance. Stricter working conditions and demands on sports journalists during the Olympics

- New Olympic sports: the mediatization of action sports through the Olympic Games 2020 Tokyo

- Simone Biles, journalistic authority, and the ideology of sports news

- Representations of gender in the live broadcast of the Tokyo Olympics

- Americans on ideological left more engaged in Summer Olympics

- Nigeria: Olympic Games a mystery for rural dwellers in Lagos

- National hierarchy in Israeli Olympic discourses

- Equestrian sports in media through hundred Olympic years. A roundtrip from focus to shade and back again?

- Reshaping the superhuman to the super ordinary: The Tokyo Paralympics in Australian broadcasting media

- Is the Paralympic Games a second-class event?

- The fleeting nature of an Olympic meme: Virality and IOC TV rights

- Tokyo 2020: A look through the screen of Brazilian television

- Is the Paralympic Games a second-class event?

- How digital content creators are shaping meanings about world class para-athletes

- How digital content creators are shaping meanings about world class para-athletes

- The male and female sports journalists divide on the Twittersphere during Tokyo 2020

- Super heroes among us: A brief discussion of using the superhero genre to promote Paralympic Games and athletes

- “Everything seemed very complicated”: Journalist experiences of covering the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games

- Representing high performance: Brazilian sports journalists and mass communication professionals discuss their philosophies on producing progressive Paralympic coverage

- Representations of gender in media coverage of the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games

With the end of arguably the most disrupted Olympiad of recent times where the novel coronavirus global pandemic has caused important changes to our relationship to sport and our ways of life in both local and global settings, by transforming the Olympic calendar through the postponement of the summer Olympic Games, and ultimately requiring all of us to appreciate the event at distance, it is now important to look back and reflect on how those disruptions materialized themselves in a place that is becoming ever more common in our lives: digital media and in particular social media platforms.

To appreciate how we have experienced the disrupted 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games it is key to initially ponder on our historical relationship to media platforms, and specifically how sport mega-events are considered nowadays predominantly as media events. During the last 150 years advances in information and communication technologies meant that time and space relationship were altered to a level where distances shrank exponentially to a point where now we all – discounting global and local digital divides – can participate together even from afar. In a way, as argued by Mark Deuze we do not live with media, but in media. And if our existence takes place within media environments is not inconceivable to imagine that the most truly global event – the summer Olympic Games – does not only exist as such because of the global reach of media – or to put in Deuze’s terms with media – but most importantly it exists in those mediated spaces that we co-habit and co-create.

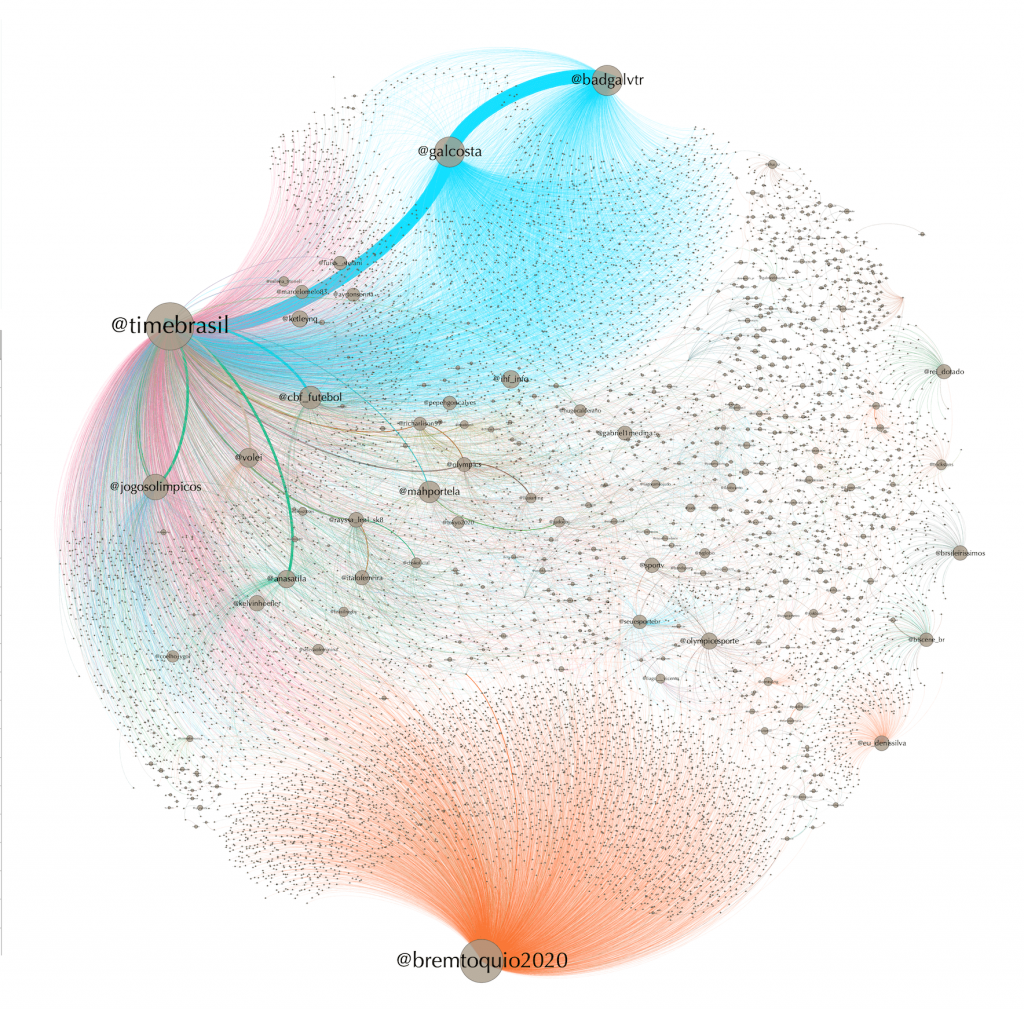

Nevertheless, this existence in media has undergone major disruptions specifically since the end of the 20th century when digital technologies – the transformation of all forms of content into 0s and 1s – and the wider adoption of Internet protocols around the world meant that a more participatory culture through two-way communication was possible. With this in mind we have automatically scraped data from Twitter to understand how Brazilians interacted with the official fan handle of the Brazilian Olympic Committee (@TimeBrasil) during all the events that took place on the 28th July. Data (Bernardamus projection – network representing user network via hashtags present in tweets) was collected between the beginning of the first event of the day until the end of the last event (see Tokyo 2020 schedule) where Brazil participated in men’s archery, men’s artistic gymnastics, women’s and men’s badminton, women’s beach volleyball, men’s boxing, women’s and men’s canoe slalom, men’s football, men’s handball, men’s and women’s judo, women’s and men’s sailing, men’s and women’s swimming, men’s table tennis, mixed double’s tennis and women’s doubles tennis, and men’s volleyball. Between those sports in the Olympic Program sport participation in Brazil is divided as follows: football (42.7%), volleyball (8.2%), swimming (4.9%) handball (1.6%), gymnastic (1.5%), judo (0.8%), tennis (0.8%), boxing (0.6%), canoeing (0.1%) (see Brazilian Government, 2013).

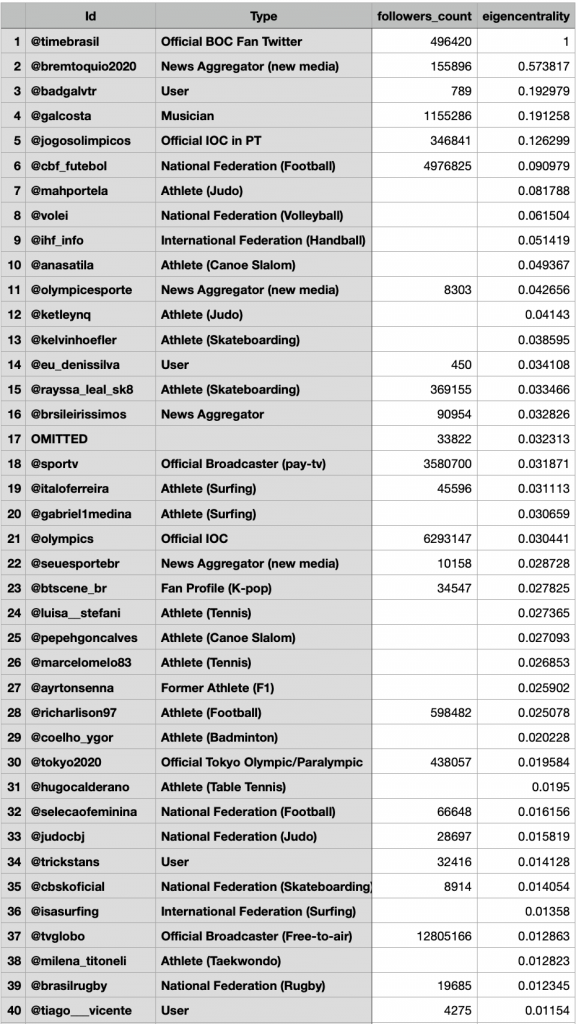

In order to check who were the most influential users in this network we ran an eigenvector centrality analysis (see Borgatti et al, 2018) which unsurprisingly showed that the sport media ecosystem has been disrupted by new digital media affordances such as the capacity for interactivity in an environment where all users become producers and consumers of content. Out of the top 21 users (#21 @olympics) only one was a traditional media outlet (#18 @sportv – pay-tv broadcaster in Brazil) while the majority were athletes (7) from multiple sports such as judo (#7 @mahportela; #12 @ketleynq), canoe slalom (#10 @anasatila), skateboarding (#13 @kelvinhoefler; #15 @rayssa_leal_sk8) and surfing (#19 @italoferreira; #20 @gabriel1medina). Our first surprise was to only encounter the first men’s football player (@richarlison97) at #28, and also how the two surfers and skaters were still relevant to this network even though their participation in the Olympic Games had ended in the 27th (surfing) and 26th (skateboarding). This possibly shows how successful the IOC was implementing some of the recommendations of Agenda 2020 and Agenda 2020+5 by incorporating those sports in the summer Olympic Games program and thus reinforcing their connection to a younger audience (see IOC, 2021).

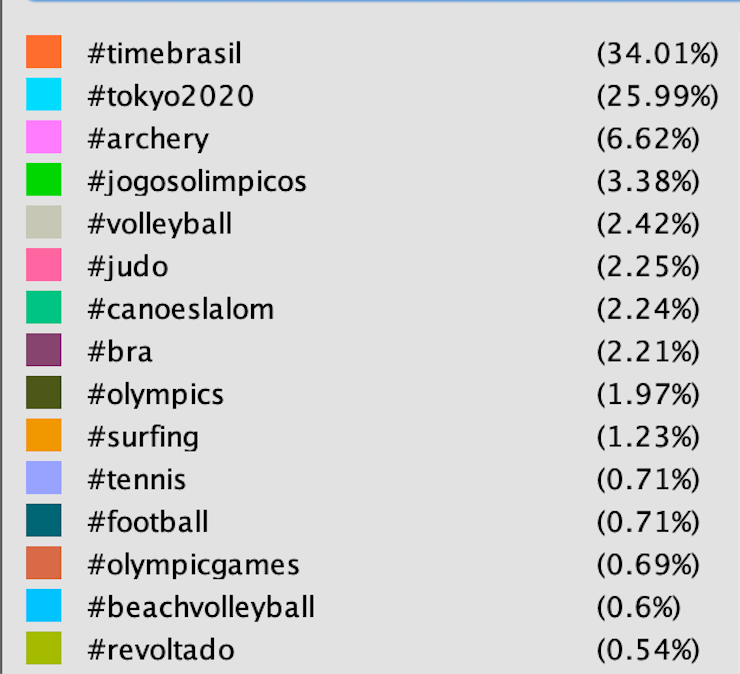

Another analysis we ran was to check the most used hashtags in this network, and to our surprise #archery (#3, 6.62%), #volleyball (#5, 2.42%), #judo (#6, 2.25%), #canoeslalom (#7, 2.24%), #surfing (#10, 1.23%), #tennis (#11, 0.71%) all appeared above #football (#12, 0.71%) which demonstrate how this social media platform provides space for sports that might be considered minority within Brazilian sporting culture.

Although all the above discussion shows how the sport media ecosystem has been disrupted by digital transformations there is one final element that is worth mentioning in terms social media platforms: the power of grassroots intermediaries in shaping the conversations (see Jenkins et al, 2013). The #3 most influential user in this network was an ordinary fan who shared a meme (wordplay between Gal Costa and Guilherme Costa – a swimmer) tagging along the famous Brazilian singer (#4, @galcosta). This tweet alone got over 400 replies, 12,000 retweets, and 100,000 likes.