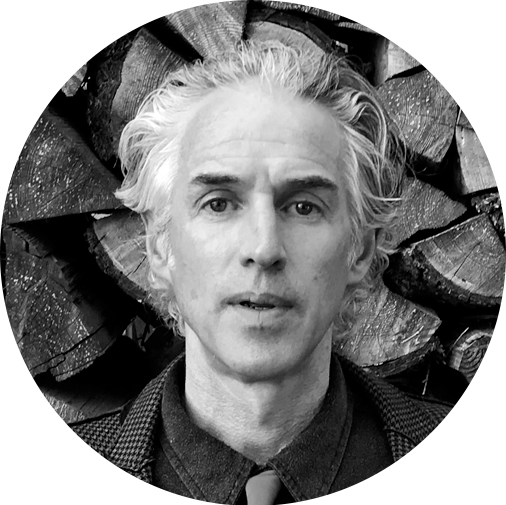

Prof Jules Boykoff

Author of four books on the Olympic Games, most recently NOlympians: Inside the Fight Against Capitalist Mega-Sports in Los Angeles, Tokyo, and Beyond (Fernwood 2020) and Power Games: A Political History of the Olympics (Verso 2016). He teaches politics at Pacific University, USA.

Twitter: @JulesBoykoff

Section 5: Politics of Sport

- Despite “Gender Equal Olympics,” focus still on what women are wearing

- The sacred space of the Olympics

- At Tokyo Games, athlete activism takes front row seat despite IOC’s attempts to silence athletes

- Forced hijab and female athletes in postrevolutionary Iran

- Pay equity and the Tokyo 2020 Olympics

- We want reform

- The revolt of the Black athlete continues

- The colonization of the athletic body

- Rooting for U.S. Olympians: Patriotism or polarization?

- The new kids on the block: Action sports at the Tokyo Olympic Games

- Black women and Tokyo 2020 games: a continued legacy of racial insensitivity and exclusion

- “A ceremony for television”: the Tokyo 2020 media ritual

- Softball’s field of Olympic dreams

- Equal remuneration for a Paralympian

- Is there space on the podium for us all?

- The Tokyo Paralympics as a platform for change? Falling well short of sport and media ‘opportunities for all’

- Tokyo 2020 Paralympics: inspirations and legacies

- What social media outrage about Sha’Carri Richardson’s suspension could mean for the future of anti-doping policies

- Now you see them, now you don’t: Absent nations at Tokyo Paralympic Games

- Will #WeThe85 finally include #WeThe15 as a legacy of Tokyo 2020?

- WeThe15 shines a spotlight on disability activism

- Activism starts with representation: IPC Section 2.2 and the Paralympics as a platform for social justice

- In search of voice: behind the remarkable lack of protest at the Tokyo Paralympics

During pockets of silence at the opening ceremony for the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics, people inside the freshly built National Stadium could hear protesters outside chanting, “Go to hell, Olympics!” and “Stop the Opening Ceremony now!” Writing in the Denver Post, Mark Kiszla noted, “All the fireworks in Japan couldn’t stop the event from being a dud. The real buzz was outside, in the street, where protesters made the beautiful noise of hearts yearning to be heard.”

The “real buzz” was the result of years of transnational anti-Olympics organizing. In July 2019, anti-Olympics activists from around the world convened in Tokyo for the first-ever anti-Olympics summit, designed to coincide with the one-year mark before the original start date of the Tokyo Olympics. The weeklong series of events included strategy-sharing sessions, public talks, and tours of Olympic areas. There was also a large mobilization in the Shinjuku district of Tokyo that attracted around 1,000 participants. Two Tokyo-based anti-Olympics activist groups—Hangorin no Kai and Okotowalink—teamed up with protesters from past Olympic cities (Pyeongchang, Rio de Janeiro, London, Nagano, Seoul), future hosts (Paris, Los Angeles), and potential bidders (Jakarta). The anti-Games group from Los Angeles—NOlympics LA—sent the largest contingent from outside of Japan, nearly twenty people.

Hangorin no Kai translates to “Anti-Olympics Group” and it has worked to live up to the name, engaging in numerous protests in the years leading up to the Tokyo Games. Born in 2013, the group has a core of around a dozen active members, with numbers climbing toward 100 for creative, playful protests and street actions. Okotowalink, which roughly translates to “No Thanks Olympics 2020,” is packed with academics and researchers who double as political organizers.

Appearing on Democracy Now! outside the Tokyo 2020 opening ceremony, activist and Kansai University professor Satoko Itani said, “the people have been frustrated actually ever since the awarding of the Olympics in 2013…Since then, with the neoliberal policies, people’s lives are getting harder and harder. And when it comes to the Olympics, it seems like there are endless resources and money.”

The day after the opening-ceremony mobilization, Hangorin no Kai organizer Misako Ichimura told me, “Protests are occurring autonomously” and in decentralized fashion across Japan. A sort of protest domino effect had emerged. She described protest plans for disparate locations—Chofu, Ariake, Yokohama—noting, “Some of these protests were organized by participants in yesterday’s demonstration, who were calling for their comrades to protest against Olympic events being held in their local area.” Protesters also targeted the five-star hotel in Tokyo where the International Olympic Committee entourage was staying. Protests continued through the end of the Games when activists mobilized during the closing ceremony.

Historically, when it comes to protesting the Olympics, the general trend is that a central entity in the Olympic city steers extant activist groups under a temporary anti-Games umbrella. As such, anti-Olympics activism tends to be an extended moment of movements rather than a movement of movements. Already-existing movements coalesce in what social-movement scholar Sidney Tarrow calls an “event coalition” marked by an upsurge in cooperation around an event—in this case the Olympics—that dissipates once the event happens, at which point dissidents return full-force to their original political focus. However, NOlympics LA, which emerged in May 2017 from the Housing and Homelessness Committee within the Democratic Socialists of America chapter in LA, has played a pivotal role in changing that: creating a transnational movement that transcends a single Olympics.

As Hiroki Ogasawara, an anti-Olympics activist and sociology professor at Kobe University in Japan, put it, no longer should we “see the anti-[Olympics] movements [as] being isolated and divided according to nations and cities because the protest is already worldwide and the Olympics inevitably involve global scale wrongdoings, too.”

IOC missteps and gaffes vis-à-vis the Tokyo 2020 Olympics opened up space to mainstream anti-Olympics arguments, as did the IOC’s bald pursuit of its own fiscal interests over global public health. IOC President Thomas Bach’s rhetoric around the delayed Games being “a celebration of humanity, for having overcome this unprecedented crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic” and “the light at the end of this dark tunnel” simply did not line up with the coronavirus facts on the ground.

Anne Orchier, co-chair of NOlympics LA, told me, “We have always known that Olympic organizers prioritize their profit margins over human life, putting both athletes and residents of host cities at considerable risk in order to squeeze out an extra million here and there. But this goofy postponement process has revealed that they also no longer care about saving face and pretending they’re interested in anything other than consolidating wealth and power for themselves, and are willing to put millions of lives at risk to do so.” Orchier was part of the contingent from NOlympics LA that traveled to Tokyo in July 2019 for the inaugural transnational summit. At the event, researcher Cerianne Robertson unveiled “Olympics Watch,” an online transnational archive of anti-Games resistance.

The Olympics have hit a reckoning point. The Tokyo Games created space to assess whether the Olympics, as currently constituted, should even exist in modern sporting life. Anti-Games groups in Tokyo—and across the world—have an unequivocal answer to that: #NOlympicsAnywhere. And as Mark Kiszla of the Denver Post put it, “For the first time, it feels as if the Olympic movement might not be too big to fail.”