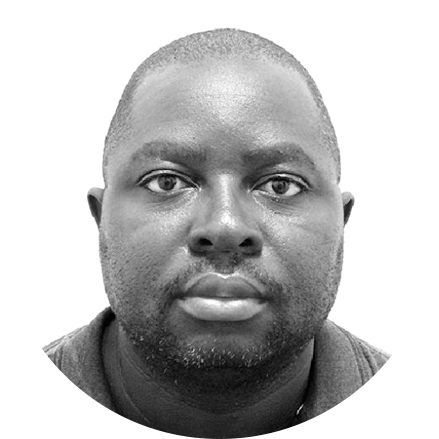

Dr Manase Kudzai Chiweshe

Dr. Manase Kudzai Chiweshe is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Social and Community Development, University of Zimbabwe. He is the winner of the 2015 Gerti Hesseling Prize for Best Paper Published in African Studies. His work revolves around the sociology of everyday life in African spaces with specific interest in football and sports studies.

Twitter: @manasekudzai

Section 5: Politics of Sport

- Despite “Gender Equal Olympics,” focus still on what women are wearing

- The sacred space of the Olympics

- At Tokyo Games, athlete activism takes front row seat despite IOC’s attempts to silence athletes

- Forced hijab and female athletes in postrevolutionary Iran

- Pay equity and the Tokyo 2020 Olympics

- We want reform

- The revolt of the Black athlete continues

- The colonization of the athletic body

- Anti-Olympics activism

- Rooting for U.S. Olympians: Patriotism or polarization?

- The new kids on the block: Action sports at the Tokyo Olympic Games

- “A ceremony for television”: the Tokyo 2020 media ritual

- Softball’s field of Olympic dreams

- Equal remuneration for a Paralympian

- Is there space on the podium for us all?

- The Tokyo Paralympics as a platform for change? Falling well short of sport and media ‘opportunities for all’

- Tokyo 2020 Paralympics: inspirations and legacies

- What social media outrage about Sha’Carri Richardson’s suspension could mean for the future of anti-doping policies

- Now you see them, now you don’t: Absent nations at Tokyo Paralympic Games

- Will #WeThe85 finally include #WeThe15 as a legacy of Tokyo 2020?

- WeThe15 shines a spotlight on disability activism

- Activism starts with representation: IPC Section 2.2 and the Paralympics as a platform for social justice

- In search of voice: behind the remarkable lack of protest at the Tokyo Paralympics

The history of black women in the Olympics is fraught with complexities that spun an intersection of gender, race, and bodily integrity. Before and during the Tokyo 2020 games, issues surrounding black women, the International Olympic Committee, and many sporting associations emerged to highlight the continued historical marginalization. This article focuses on various instances where the IOC and affiliated national organizations were involved in controversies that negatively affected the participation of black women in sporting activities. The policing and exclusion of African female bodies from the Olympic games has to be understood within a historical context in which black women have continually fought for their right to exist and be present in sporting spaces. In any case the Olympic International Committee before the games reiterated the ban on Black Lives Matter apparel and symbolic protests, citing IOC Rule 50. Many women’s soccer teams however went on to kneel as a symbolic support to the movement.

Naturally occurring testosterone levels, sexuality and womanhood at the Olympics

The stories of African female athletes with naturally occurring testosterone levels builds on historical narratives of bodies that do not just fit into Olympics’ (western) neat gender categorizations. Before the Tokyo 2020 games, Caster Semenya, Aminatou Seyni, Margaret Wambui, and Francine Niyonsaba have been barred from competing in their preferred Olympic event because of their natural testosterone levels. Naturally occurring testosterone has been crafted as an unfair advantage, which in isolation would make sense if the whole idea of sport was not built on disparities in natural abilities. Sports scientists such as Ross Tucker however argue that high testosterone alone cannot justify banning athletes for an advantage among elite sportswomen. In June 2021, two more young athletes from Namibia, Christine Mboma and Beatrice Masilingi were banned from running the women’s 400-metre race. Both athletes only knew about the condition when they were tested at a training camp in 2021 in Italy. Christine Mboma went on to win the 200 metres race but the ‘controversy’ of her sexuality and testosterone was only beginning. There have been calls by some European officials to have further tests to prove that she is a ‘woman’. The 2018 World Athletics hormone regulations were mainly targeted at intersex athletes who are said to an unfair competitive advantage in track events ranging between 400 metres and 1500 metres. Critics of this rule however believe that it is ‘a toxic combination of racism and transphobia’, it has also ‘the appearance of World Athletics “targeting” African women, based on their supposed masculine features, once they start excelling on the global stage.’ A Cameroon official concluded that, ‘The majority of athletes affected by the regulations are from the global south and for Africa these regulations remind us of the difficult and dark past of racial segregation.’

Black women’s mental health and the Olympics

Another key point before and after the Tokyo 2020 games is the issue concerning mental health of black female athletes. For Simone Biles (probably the best gymnast of her generation), the moment she withdrew citing mental health, the wolves were waiting. Portrayed as a fickle, weak and nervous coward like Sha’Carri Richardson before her who had smoked marijuana dealing with bad news and Naomi Osaka who withdrew from the French Open. How dare they shatter our carefully modelled epitaph of the “strong black woman.” An epithet built on stereotypes meant to romanticize and ultimately force acceptance of the historical exclusion, poverty and struggle for women of color, and a history of bearing the multiple burdens of oppressive white racism, capitalist exploitation and patriarchy. The lack of compassion and benefit of doubt was astounding from mainly white and some black commentators without fully understanding the various complexities involved with Biles’ struggles with ADHD.

Black hair and the swimming cap controversy

The controversy of the swimming cap was a classical analysis of how “white tradition” in sporting spaces have resisted bodies that do not neatly fit into their narrow categories. It is surprising that in 2021 there are some within global sporting organisations who are racially insensitive to the point of codifying exclusion of people on the basis of hair. The controversy started when swimming caps designed for natural black hair by a company called Soul Cap was banned by International Swimming Federation (FINA). FINA was forced to reconsider the ban after widespread outcry globally. It is this stubbornness built on the privilege of owning these spaces they have seen even white women facing sexist attitudes such as the Norwegian beach volleyball team.

Conclusion

The Tokyo 2020 games highlighted the continued challenges facing black women to achieve respect, inclusivity, and equal participation, particularly the construction of sporting bodies from a narrow, mainly white and partriachial lens. The intersection of racism and sexism within sport has meant an increasing number of black women cannot compete, especially African women like Caster Semenya simply because they do not present their gender in the manner prescribed by largely western partriachial systems that still dominate institutions such as the Olympics.